-

Artworks

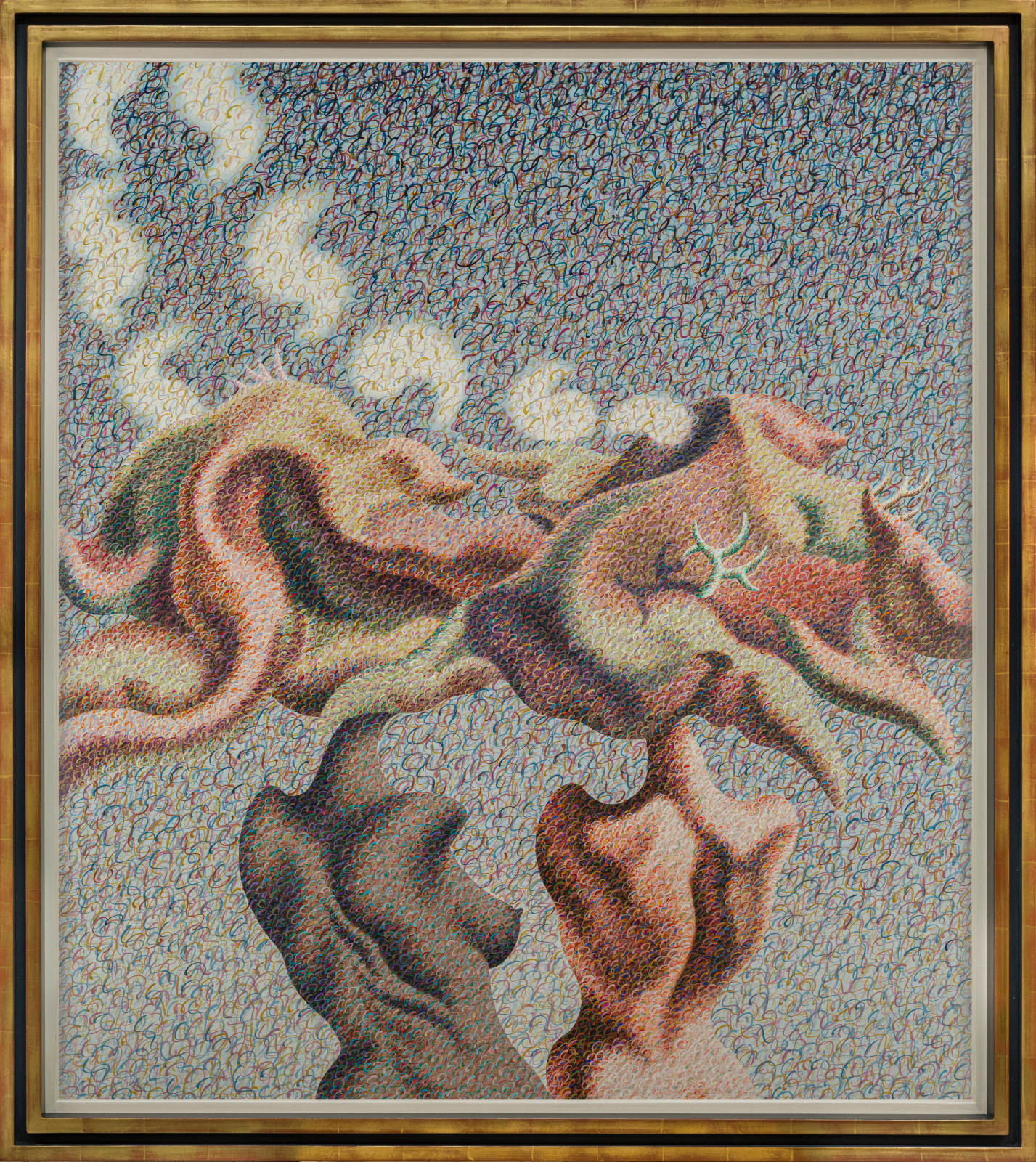

Henry Orlik b. 1947

THE FORTRESS THAT THE WIND AND RAIN CREATEDAcrylic on canvasImage: H. 125cm x W. 110cm; H. 49 x W. 43inWith artist's stamp versoWB2695Copyright The ArtistFurther images

In the pantheon of contemporary figurative painting, few works achieve the psychological intensity and formal complexity of Henry Orlik's The Fortress that the Wind and Rain Created. This canvas is...In the pantheon of contemporary figurative painting, few works achieve the psychological intensity and formal complexity of Henry Orlik's The Fortress that the Wind and Rain Created. This canvas is not just an aesthetic achievement, but a profound philosophical manifesto, presenting a meditation on intimacy, vulnerability, and resilience that transcends its deceptively simple premise of two female figures rendered with their backs to the viewer.

The composition's revolutionary architecture emerges from Orlik's deliberate rejection of facial representation, a philosophical stance rooted in his belief that visages explain everything, thereby limiting interpretive possibility. Moreover, he, like the Ancient Greeks, believed that clothing concealed whilst the truth is allegorically revealed by the naked form. Through this he extends ideals preserved from the Ancients and continued through artistic masters such as Michelangelo, Titian and George Frederic Watts. Thus, the expressive burden falls upon the figures' dorsal anatomy, which becomes topographical maps of meaning. The left subject's spine curves with geological precision, with vertebrae suggesting both human structure and mountain ridge. Her companion's shoulders form crystalline planes that catch light like weathered stone, reinforcing the titular metaphor of bodies as fortifications shaped by temporal forces.

Orlik's treatment of hair achieves particular significance within this strategy. The luxuriant massed tresses rising from both subjects function as painterly tours de force, demonstrating what he terms follicular infinite manipulability. Within these cascading forms, multiple readings emerge simultaneously: ocean waves crash against imagined shores while profile faces peer from amber depths. A giant ear materialises within the coiffure, suggesting the act of listening that permeates the canvas. Most remarkably, what initially appears as feminine styling reveals itself as avian talons; manicured digits transform into predatory appendages, reinforcing themes of beauty concealing danger. Careful examination reveals a distinct goat emerging from the elaborate structure, adding profound mythological resonance.

This caprine presence connects the piece to ancient traditions of Pan and fertility spirits, becoming another watching entity within Orlik's primordial landscape. The beast, associated with Dionysian ecstasy and earth elements, represents the untamed aspect lurking beneath civilised surfaces, a horned deity overseeing feminine mysteries.

Within this complex iconographic programme, the most subtle yet most significant symbolic forms emerge from the follicular organic architecture. Following the Surrealist tradition of embedding anatomical references within landscape and portrait imagery, as seen in the oeuvres of Leonora Carrington, Dorothea Tanning, Remedios Varo and Ithell Colquhoun, Orlik incorporates intimate anatomical symbols within the upper reaches of both coiffures. These vulvar references evoke Giuseppe Arcimboldo's composite portraits while also connecting to broader traditions of hidden symbolism in European painting. Rather than Georgia O'Keeffe's direct, iconic presentation of natural forms as metaphors for feminine experience, Orlik's approach proves archaeological. These discoveries are embedded within his complex visual mythology, reinforcing central themes of generative power and the compulsion and complexity of desire, while maintaining his characteristic interpretive openness.

The mysterious silhouetted visage emerging from this follicular landscape introduces the composition's most enigmatic element. Positioned between the subjects yet belonging to neither, this profile appears to draw upon a pipe, exhaling white vapour that mingles with the atmospheric background. The countenance suggests the anthropomorphised spirit of the land itself: a wise, weathered presence evoking a Native American elder sending smoke signals of ancient knowledge or ecological warning.

This reading transforms both women into sirens of the earth, seductive entities that embody humanity's complex relationship with the natural world. They become simultaneously protectors and betrayers of the landscape, their beauty masking potential destruction. The smoking entity's placement suggests the land's patient observation of human behaviour, its ancient wisdom expressed through ritual practices deeply connected to Indigenous spirituality and communion with natural forces. Together with the caprine form and anatomical symbols, these watching spirits create what might be termed a "council of observers", ancient forces witnessing the eternal dance between human desire and natural consequence.

Historically, this interpretation aligns Orlik's practice with the distinctive Surrealist engagement with Indigenous and archetypal imagery. The composition evokes Max Ernst's Two Children are Threatened by a Nightingale (1924), in which mysterious forces observe human subjects; however, Orlik's treatment proves far more psychologically nuanced. The anthropomorphised landscape tradition finds potent expression in Wolfgang Paalen's Cosmic Joy (1938) and Roberto Matta's The Earth is a Man (1942), which explicitly conflates geological and human anatomy. Orlik's work, in this context, can be seen as a continuation of this tradition, but with a unique contemporary twist.

The smoking pipe motif evokes Oscar Domínguez's Nostalgia of Space (1939), featuring mysterious profiles exhaling cosmic vapours. It connects to the broader Surrealist fascination with shamanic practices explored by Kurt Seligmann. Orlik's innovation lies in domesticating these cosmic themes: bringing the archetypal into intimate, contemporary space while maintaining mythic power. His positioning of subjects with their backs turned also recalls Caspar David Friedrich's Romantic sublime, particularly Wanderer above the Sea of Fog (1818). However, where Friedrich's protagonist contemplates an infinite landscape, Orlik's paired subjects exist in dialogue with, and become, the sentient earth itself.

The temporal duality, which simultaneously evokes 1980s Dynasty glamour and timeless mythological entities, situates the canvas within postmodern historical consciousness. These women embody their era, stick-thin characters with voluminous styling and sharp shoulders, yet transcend periodisation to become eternal, bird-like sirens who appear both impregnable and predatory. And yet, they are armless and as powerless as the statue of the Venus de Milo. Thus, Orlik, a champion of the “intelligence” of the female psyche which he saw as a vital assuagement of male domination and violence, evokes womanhood in a male-dominated society as both powerful muse and powerless handmaiden. They are evocative of the Handless Maiden motif: as sirens their wings have not just been clipped but removed. They epitomise Orlik's ability to synthesise contemporary observation with archetypal resonance.

The Fortress that the Wind and Rain Created resonates with profound autobiographical and philosophical dimensions, illuminating Orlik's unique position as both creator and observer. The metaphor of fortress-building through elemental exposure speaks to multiple layers within his lived experience and aesthetic philosophy. As the only child of Polish-Belarusian refugees arriving in post-war England, Orlik embodies cultural displacement: identity forged not through roots but through adaptation to foreign winds and rains. The fortress becomes a metaphor for protective psychological structures that those who must create rather than inherit a belonging construct.

The gendered dynamic assumes poignancy when considered alongside Orlik's role as his mother, Lucyna's, treasured only son. The two subjects, observed but not possessed, may represent the complex relationship between aesthetic creation and feminine presence in the life of a son who chose art over conventional domestic arrangements.

Their turned backs suggest both intimacy and distance: the eternal mystery of the feminine as both artistic muse and separate, unreachable being. Philosophically, this ecological reading deepens the composition's interrogation of humanity's relationship with the natural world. The dorsal presentation creates barriers; we cannot know these entities completely, just as we cannot fully comprehend our impact on the earth that observes us. The title's reference to elemental forces assumes urgent significance when read as environmental powers shaping both the landscape and human consciousness.

As Orlik's 1985 theoretical writings reveal, he treats 'each shape as if it were a world in itself,' affirming 'its existence even to the invisible depth of its microscopic agitations of atoms.' This philosophical approach to his art sheds light on Orlik's intention to create a work that is not just a painting, but a world, inviting viewers to explore its depths and implications.

Furthermore, Orlik believes there are no empty spaces. Thus, the shaped ‘spaces’ between objects in his paintings are as important as the objects themselves. They teem with his excitation brushstrokes, symbolic of the quantum field. Here, the space between the women’s torsos is shaped like a womb and birth canal. The ‘space’ is filled with potent creative potential which Orlik sees as evolution. He uses a similar motif in Mermaid in Central Park, where the pool in front of the ‘Mermaid’ is her womb, alive with potential.

The small white root fleeing from the elaborate coiffure provides the canvas's most whimsical yet significant detail. This clear homage to Hieronymus Bosch's John the Baptist in the Wilderness (c. 1489, Museo Lázaro Galdiano, Madrid) introduces themes of spiritual contemplation displaced by feminine sensuality. The root's contemplative territory has been usurped, and he flees as his dark shadow escapes in the opposite direction. This flight becomes a visual pun on the displacement of ascetic values by aesthetic ones, suggesting a broader cultural shift from religious to secular modes of transcendence.

For Orlik himself, this canvas represents far more than aesthetic achievement: it embodies profound meditation on chosen solitude and the creative life. His career-long dedication to art, over conventional relationships, reflects not an absence but a presence, a complete devotion to exploration as a spiritual practice. The piece embodies what might be termed "elective monasticism": the creator's choice to channel life energy into a creative rather than procreative legacy.

The follicular landscapes gain additional significance when viewed through this lens. Orlik's fascination with such material, "you can do so much with it," he notes, becomes a metaphor for creative potential itself. The luxuriant masses transforming into talons, waves, listening ears, sea-creatures, anatomical symbols, and watchful beasts represent imagination's fertility: beauty creating meaning rather than progeny. Like a visual palimpsest, each viewing reveals new, hidden forms; the coiffure becomes a primordial landscape where archetypal spirits emerge to observe human interaction.

Orlik’s avoidance of facial representation reaches a logical conclusion in subjects whose backs prove more expressive than any frontal view could achieve, suggesting that true intimacy lies in what remains unseen, unexplained, and eternally mysterious. Orlik's Wall Street apartment view reveals how daily encounters with urban architecture influenced his understanding of animate presence. The buildings that "watched" him provided companionship that required neither explanation nor conventional commitment: a relationship with the world based on observation and response rather than possession or traditional intimacy.

The Fortress that the Wind and Rain Created ultimately stands as both a masterpiece and a philosophical statement about alternative forms of human completion. In its formal sophistication and conceptual depth, the canvas achieves that rare status of contemporary achievement, rewarding both immediate appreciation and sustained contemplation.

Like the elemental forces of its title, the piece gradually shapes consciousness, leaving viewers transformed by its strange, persistent beauty, much as the solitary creator shapes meaning through sustained engagement with surrounding mysteries.

The composition's enduring power lies in its ability to maintain interpretive openness while delivering visceral impact. These entities exist in perpetual becoming, woman and landscape, contemporary and eternal, vulnerable and impregnable, observed and observing. They embody Orlik's understanding that human identity operates through continuous metamorphosis rather than fixed essence, whether through conventional relationships or the profound intimacy possible between creator and world. In refusing to show us their faces, he creates space for endless speculation about interior lives, transforming viewers into active participants in psychological drama while suggesting that the deepest forms of human connection may transcend traditional boundaries entirely.

Join our mailing list

Be the first to hear about our upcoming exhibitions, events and news

* denotes required fields

We will process the personal data you have supplied to communicate with you in accordance with our Privacy Policy. You can unsubscribe or change your preferences at any time by clicking the link in our emails.