-

Artworks

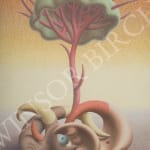

Henry Orlik b. 1947

GROWTH - Ltd Edition PrintArchival quality giclee limited edition print

Digitally signed and numbered

Edition of 500Image: H. 58 cm. x W. 43 cm.

Framed: H. 66 cm. x W. 50.5 cm. x D. 4.5 cm.

Unframed £ 650.00

Framed £ 795.00WB1640Copyright remains with the Artist and Winsor Birch Ltd.Further images

In Growth Orlik depicts a tree whose roots seem to be two entwined, contorted and writhing, flesh-coloured bodies – one slightly darker than the other. The two bodies seem to...In Growth Orlik depicts a tree whose roots seem to be two entwined, contorted and writhing, flesh-coloured bodies – one slightly darker than the other. The two bodies seem to share a head, which is also an eyeball. They conjure images of frolicking sea-creatures like sealions or dolphins playing with balls at aquariums. However, they have the suggestion of human bodies, so that the female figure on the right has her navel upwards but then the back becomes the front as her breasts are on the other side of her torso. Both figures have two short ‘arms’ which are also the heads of a hammer-head shark or the divided tail of a dolphin. Their bodies seem to end in curved horns or tails, or maybe these spikes are their heads. One curved tail-horn is coloured orange (with an extra orange spike peeping out suggestively at the darker figure’s groin area) and two are pale yellow which echo the colour of the soft light in the background, which then progressively becomes more orange with a greater depth of colour towards the top of the image. The main red stem of the ‘tree’ grows upwards splaying out into a web of branches which are also a network of veins and arteries. At the top of the tree is a solid, rounded, green canopy which is pierced by red spikes – the continuation of the network of branches which seem to grow out of it, reaching out, like antennae, into the universe.

Like all sharks, hammerheads have electroreceptory sensory pores called ampullae of Lorenzini. These sensory pores lead to sensory tubes, which detect electric fields generated by other living creatures, allowing them to find prey. These electric fields are suggestive of Orlik’s excitation brushstrokes and perhaps here the ‘antennae’ emanating from the canopy of the tree send signals down to their roots and out into the universe – allowing them to find their mate.

The tree is suggestive of the Tree of Life out of which all life is mythologically generated. Here, Orlik (as he does in several of his paintings) is bringing in the idea of evolution and how the passage of ‘cosmogenesis’ leads to increasingly elaborate organisms from ‘subatomic units to atoms, from atoms to inorganic and later to organic molecules, thence to the first subcellular living units or self-replicating assemblages of molecules, and then to cells, to multicellular individuals, to cephalised metazoan with brains, to primitive man, and now to civilised societies.’ (Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, The Phenonemon of Man, 1972 (first published 1955), p. 15). Thus, the tree becomes the phylogenetic tree which shows the evolutionary history of species, indicating the common ancestry of the shark and the human. From this perspective, ‘the world appears like a mass in process of transformation’. (Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, The Phenomenon of Man, 1972, (first published 1955), p. 52)

Join our mailing list

Be the first to hear about our upcoming exhibitions, events and news

* denotes required fields

We will process the personal data you have supplied to communicate with you in accordance with our Privacy Policy. You can unsubscribe or change your preferences at any time by clicking the link in our emails.