Henry Orlik b. 1947

-

-

Henry Orlik, FIGHTING SKYSCRAPERS - Print£ 2,995.00

Henry Orlik, FIGHTING SKYSCRAPERS - Print£ 2,995.00 -

Henry Orlik, WORKERS ROLLING INTO NYC - Print£ 2,950.00

Henry Orlik, WORKERS ROLLING INTO NYC - Print£ 2,950.00 -

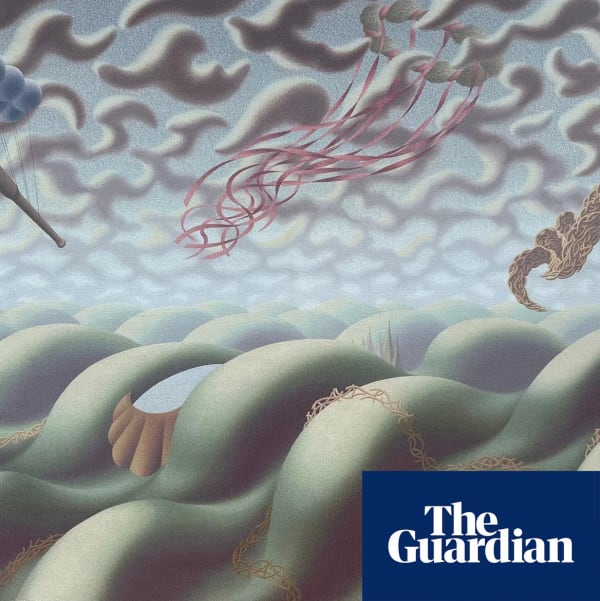

Henry Orlik, The Parting - Print£ 2,950.00

Henry Orlik, The Parting - Print£ 2,950.00 -

Henry Orlik, Yellow Galleon - Print£ 2,950.00

Henry Orlik, Yellow Galleon - Print£ 2,950.00

-

Henry Orlik, Parachute - Print£ 2,950.00

Henry Orlik, Parachute - Print£ 2,950.00 -

Henry Orlik, CANNON BALLOONS - Print£ 2,950.00

Henry Orlik, CANNON BALLOONS - Print£ 2,950.00 -

Henry Orlik, THE SECRET GARDEN - Print$ 800.00

Henry Orlik, THE SECRET GARDEN - Print$ 800.00 -

Henry Orlik, WINOS IN CENTRAL PARK NYC (Drawing) - Print£ 795.00

Henry Orlik, WINOS IN CENTRAL PARK NYC (Drawing) - Print£ 795.00

-

Henry Orlik, DEFEAT (AEROPLANE OVER LA) - Print£ 795.00

Henry Orlik, DEFEAT (AEROPLANE OVER LA) - Print£ 795.00 -

Henry Orlik, BEAUTY AND SHARKS - Print$ 800.00

Henry Orlik, BEAUTY AND SHARKS - Print$ 800.00 -

Henry Orlik, END OF AN AFFAIR - Print$ 800.00

Henry Orlik, END OF AN AFFAIR - Print$ 800.00 -

Henry Orlik, DREAM - Print$ 800.00

Henry Orlik, DREAM - Print$ 800.00

-

Henry Orlik, REST - Print$ 800.00

Henry Orlik, REST - Print$ 800.00 -

Henry Orlik, KITE - Ltd Edition Print$ 800.00

Henry Orlik, KITE - Ltd Edition Print$ 800.00 -

Henry Orlik, NY SKYSCRAPERS - Print£ 695.00

Henry Orlik, NY SKYSCRAPERS - Print£ 695.00 -

Henry Orlik, BEVERLY HILLS - Print£ 795.00

Henry Orlik, BEVERLY HILLS - Print£ 795.00

-

-

Biography

Henry Orlik was born in Ankum, Germany on 6th January 1947. During the war, Henry’s mother, Lucyna Polch (1928-2002), was taken as slave labour by the Nazis from her village, Niacholsty near Brest, on the Belarus-Poland border, when Brest was captured by the Nazis in 1941 as part of Operation Barbarossa. By the end of the war, half of Belarus’s population had been killed or deported. She was sent to a farm near Ankum in Western Germany, where she had to labour in exchange for food. She was a determined young girl, and at one point attempted an escape with a friend but was caught and returned to the farm.

Henry’s father, Jozef Orlik (1923-1998), was born into a family of glassblowers in Kraków, Poland. When the Nazis occupied the city in September 1939, life changed overnight. The Orlik family had to steal food from the Germans to survive and family history records that Jozef was hung up by his black hair and beaten by the Nazis because they thought he was Jewish and stealing food. It was “a shaping experience.” Jozef wanted to join the Polish underground but was turned down as he was only sixteen. He was betrayed to the Germans by a fellow Pole for having a radio and like many Poles, was conscripted into the German army. He was taken through France where he escaped and joined the Franco-Polish underground before making his way to England. From there he was sent to Scotland to train as a paratrooper and served with the 1st Polish Independent Parachute Brigade during Operation Market Garden at the Battle of Arnhem in September 1944 and subsequently took part in the advance into northern Germany. After the war, he met Lucyna, who had been freed and billeted at a moated castle near Ankum. Following their marriage, Henry was born there. Jozef had to fetch a German doctor at gunpoint after the doctor refused to attend the birth of a Polish baby.

Like many Poles, the Orliks decided to travel to England under the Polish Resettlement Scheme rather than risk returning to their Soviet-occupied homeland. Lucyna and the four-month-old Henry travelled with other women and families to England on the Queen Elizabeth in early 1948. They had no belongings and, curiously, the only item that Lucyna brought with her was a set of antlers taken from the walls of the castle. When asked why, Henry stated, “it was because they are alive, the antlers are alive, like us”; antlers or antler-like trees later featured in several of his paintings. Jozef was still in the army, and the family was moved between several resettlement camps before arriving at Fairford Camp, in Gloucestershire when Henry was around four years old. From here, Henry was sent to board at St Francis Xavier School in Lower Bullingham, Herefordshire, a Polish boarding school run by the Marian Fathers as Jozef had a strong desire to “make me Polish”. He recalls arriving at the school, the fear of being left there and how his mother hid her tears at their parting. (“She was tough; she knew how to survive.”)

School photographs show Henry as a good-looking, stocky, young boy with unruly hair. His school reports reveal a well-mannered, shy boy who was hampered by his lack of English but whose art was “outstanding” and showed “considerable promise” while his arithmetic indicated “difficulties,” a problem that plagued him throughout his life. Henry recalls the school as being in a beautiful part of the world, but it was strict and disciplined, and many of the teachers were monks. Some of the teachers had been in concentration camps and “some were paedophiles” Henry disclosed though he gave no details, adding only that all experiences are good because they teach you to survive. There was Polish dancing, which Henry hated, mainly because it was an all-boys’ school and so they dressed some of the younger pupils, Henry included, as girls.

He felt the humiliation strongly. Henry’s parents paid for his schooling by working outside the camp and travelled daily by bus to their work: Lucyna on a farm, and Jozef at Pressed Steel in Swindon, which he helped to build and where he subsequently found lifelong employment. During the holidays from school, Henry, along with other children, was looked after by trained nurses in the camp, while his parents were at work.Henry’s first clear memories are of Fairford. They are good memories, “learning memories”, tinged with the nostalgia that gives childhood a golden glow of eternal summer; he recalls “feeling free when you went beyond the fence” of the camp, to roam and swim in the rivers in the idyllic countryside. He recalls the cinema which showed all the recent releases from Hollywood, given to the camp by the American Air Force base nearby; and the large theatre and the church built from the Nissan huts; of everything being “round” and “curved”, the walls and ceilings of the Nissan huts, the barracks in which the families were housed. They felt “space age”. The Orlik’s barracks were divided into two bedrooms, with a kitchen and a coal stove. There was no running water in the huts but there was a communal toilet and shower block. There were trips for the children including to Bristol Zoo and Henry has a photo of him riding an elephant. It was a world contained within a wider world, and Henry recalls feeling free and unbound but his memories are tinged by the underlying menace of camp reality. This was the reality of a fear which came from displaced people carrying their wartime experiences with them: soldiers who did not want to, or could not, “acknowledge the reality of their existence”; people quarrelling and fighting; the “noise behind the toilet block” that his parents complained about; shared spaces with people from concentration camps who were deeply troubled and who the children “learnt to avoid” as well as the many “crooks”, and people “on the make”, trying to get on, to make something of nothing. “You got a sense of the people who you can trust; you had to be on your wits, to move away.” It was paradoxical, a dog-eat-dog world, surrounded by beautiful rolling countryside and children innocently playing in the midst of it. It was hard to interpret for a sensitive boy trying to make sense of the world.

The family moved to Daglingworth Camp in 1958 when Henry was eleven. This was a smaller camp in the undulating landscape of the Cotswolds. Today there is no memorial, sign or trace of a Polish camp in this quintessential English village. Henry was determined to attend an English school and not continue at the Marian Brothers senior school in Henley where his father wanted to send him. He begged his mother to let him try an English school and fortunately, she fought for him, securing his place at Cirencester County Secondary School, which he travelled to by bus.

He felt liberated after the restrictive regime of his previous Catholic school. But from this time, Jozef became even more distant, “nasty,” as Henry put it, disappointed that his son showed no willingness to become the Polish boy he wished him to be. According to Henry, his father never spoke about his war experiences, was meticulous in his work and never had a day off sick; but he drank heavily and there was often shouting in the household.In 1963, the family visited Kraków together when Henry was sixteen. He recalled having nothing in common with his Polish relations and little interest in them. He remembers an old man, probably his grandfather, shaking his hand and crying, which he didn’t like. “I didn’t want to know any Poles because they were foreign to me. They thought differently about things, had different experiences.” The man who betrayed his father to the Nazis was still living in the locality and had to “go on holiday” to avoid a confrontation with Jozef. Henry recalled a similar paradox to that of the resettlement camps. He saw the intellectual historic city famous for its beauty and culture, but on the outskirts was Auschwitz, which none of his relations mentioned.

Henry visited Belarus with his mother to see her family and attended his only Russian Orthodox service there, among people “who dared to go.” The service “was long” but he liked the icons, “they were alive”. He recalled visiting a museum in St Petersburg with his mother filled with icons that seemed “dead,” because they had been removed from their proper setting. He remembered the overarching sense of mistrust: “the people were all watching each other”. His grandmother had once owned land, but it had since been absorbed into a collective farm, and she was allowed only a single cow. He never asked what had happened to his grandfather – it was something no one talked about. Everyone drank and Henry recalls being continually drunk on horrible vodka. But Lucyna was happier there, different from how she was in England where “she lived in fear of the Poles” who had never completely accepted her because they saw her as Russian.

Henry describes how his mother was caught in the middle of arguments between him and his father, and he was caught in the middle of theirs. Eventually Henry and Jozef avoided each other, with Henry living upstairs and his father downstairs. His father was moody and drank, frustrated that Henry could not fulfil the role he wished for him. “Maybe that’s why I’m a surrealist. A father who didn’t want to know ...”. Lucyna compensated where she could, “She was brave, but it was hard for her. She had to be quiet, stay in the background.” “She was unbelievably strong; where did she get that strength and wisdom?” When asked what rank his father had been in the army, Henry didn’t know, but laughed and said, “A general ... a general in our house.” “He spent his time between their army and our army; it was all he knew.” Jozef wanted to return to Poland and occasionally Lucyna wanted to as well, but they changed their minds. They saw life under the Soviets, how they would have to restart, and it was not a realistic choice. “It would be a fantasy. Real life was here.”

Henry showed immense promise in his art and in 1964 he enrolled at Swindon Art College where he studied for three years, continuing his studies at Gloucestershire College of Art, Cheltenham between 1966 and 1969. After that “you had to choose a profession” and his mother wanted him to be an architect, his father wanted him to get a job, to earn a steady income. Henry only wanted to be an artist and had a painting accepted for the Royal Academy Summer Exhibition in 1971. He moved to Evelyn Gardens in South Kensington, an area he liked because of its beautiful buildings. He started to make a name for himself, having a highly acclaimed one man show at the world-renowned Surrealist Art Centre, Acoris, in Brook Street in 1972 and participating in the mixed Surrealist Masters exhibitions in 1972 and 1974 exhibiting alongside Surrealist masters such as René Magritte, Max Ernst, Giorgio de Chirico and Salvador Dalí. Roland Penrose visited him in his flat and admired his paintings.

In 1978 he had a solo exhibition at the Drian Galleries, owned by the Polish artist Halima Nalecz, whom Henry disliked and at the Obelisk Galleries. It was a heady, exciting time in London and Henry did his best to make sales and charm clients, though he was often bored by people. He attended parties with fellow artists but, “it was all about getting drunk; that was the reason for them”.

During the 1970s, Henry made several visits to Poland and Belarus and one extended stay in Poland where he lived in Warsaw for five weeks. He found the city to be like a “stage set”, the centre had been rebuilt after the war, but some buildings were still pock-marked with bullet holes. He visited Berlin in 1976 and remembers Checkpoint Charlie. All the while, he visited galleries and left them slides of his work in the hope of exhibitions. Ambitious, he did the same in Paris, even sending slides to Japan, but nothing came of it.

Pavlik Stooshnoff, a flamboyant Pole, took over Acoris’s premises in Brook Street, after Von Kessel, the owner of Acoris declared bankruptcy (and was subsequently jailed for fraud). Henry recalls Stooshnoff organising a private dinner for him at Blake’s, Anouska Hempel’s hotel, where all “the artists and famous people hung out”. Stooshnoff introduced Henry to Beverly Coburn, the ex-wife of James Coburn, and they hit it off. She bought a couple of his paintings and invited him to stay with her in Beverly Hills. Henry visited New York in 1979 for a couple of weeks and decided to return to America the following year to stay for a couple of months at Beverly’s son’s house while he was away. Henry disliked the Beverly Hills lifestyle which he saw as people imprisoning themselves in gated communities. The parties bored him, and he hated the petty hierarchies and how millionaires would “lie around snorting coke”, “it was a waste of time”. He felt controlled and avoided the parties so he could concentrate on painting, eventually moving to New York in 1981, remaining there until 1985.

We have Lucyna’s letters to Henry from his time in New York. They are simple, affectionate letters which express a mother’s concerns, words of love and encouragement to her beloved son, whose art she did not understand. She would try to relieve his concerns and explain the money she was sending to him. Lines leap out from her letters written in Polish, explaining how hard life can be for an honest man; how he must pursue his dreams but avoid overwork, “it reflects on the paintings”; that his time hasn’t come yet (“everything has its time, just do not worry”); that he must explore what is important to him; go to the Park, sunbathe and relax because winter is coming; eat lots of fresh fruit; that her belief was God will reward him; telling him “money is a pile of notes, and tomorrow there is none”; moreover, he must have courage. One letter reveals that she did not receive a letter from him for two years (although he sent her tape recordings) and when she did receive one, she read it ten times.

Henry returned to London in 1985, exhausted by New York and struggles he faced in selling his work. He managed to find a flat in Redcliffe Square, drawn by its architecture, its proximity to museums and galleries, and above all its tall ceilings, which allowed him to paint large “human-scale” canvases. For a time, he continued to try to sell his work but became ever-more disillusioned with the art world and retreated from public life to concentrate on painting. He would bring his finished canvases, rolled up in tubes, by coach, to his parents’ house where he would store them. They remained in their house after their deaths and have only recently been revealed. Henry, himself, has not seen them in years.

In 2018, the locks of Henry’s London flat were changed without his knowledge, and he was unable to enter the premises. This devastated him. He returned to live in Swindon and had a debilitating stroke in 2022. He was in hospital for many months before he was able to return home.

-

Exhibitions

-

The Lost Surrealist: Henry Orlik's Quantum Revolution

Swindon 24 Oct 2025 - 14 Mar 2026Read more -

Henry Orlik: Surreal Metropolis

New York 17 - 29 Jun 2025Read more -

Henry Orlik: Cosmos of Dreams Part Two

Marlborough 23 Aug - 17 Sep 2024THIS AUCTION HAS CLOSED Henry Orlik and his advisors have been positively overwhelmed with the number of visitors that have travelled so far and visited the second selling exhibition at...Read more -

Henry Orlik: Cosmos of Dreams

London 9 - 20 Aug 2024In 1974 Henry Orlik’s (b.1947) work was included alongside great Surrealist artists such as René Magritte, Yves Tanguy and Salvador Dali in Surrealist Masters (Acoris, The Surrealist Art Centre, Brook...Read more

-

-

Press

-

A Forgotten Surrealist's Paintings Return to New York

The New Yorker, June 17, 2025 -

Reclusive Surrealist Painter Is Searching for His Lost Masterpieces

Smithsonian Magazine, February 28, 2025 -

Artist Henry Orlik offers £50,000 reward for return of missing Surrealist works

Antiques Trade Gazette, February 24, 2025 -

Reclusive artist offers £50,000 reward for life’s work lost

The Times, February 22, 2025 -

£50,000 reward for Henry Orlik's missing works

BBC, February 18, 2025 -

The great artist recluse and his 78 missing paintings

BBC, September 22, 2024 -

Exhibition of Surrealist Master, Henry Orlik at Marlborough’s Little Gallery

Marlborough News, September 9, 2024 -

Henry Orlik exhibition in Marlborough: a unique gateway to the works of a surrealist master

Marlborough News, August 17, 2024 -

Spectacular Surrealism

euronews, August 10, 2024 -

A Disillusioned Surrealist Art Star Is Making a Comeback—50 Years Later

Artnet News, August 6, 2024 -

Reclusive Artist Henrik Orlik Enters the Spotlight

ARTnews, August 5, 2024 -

Reclusive artist to show ‘extraordinary’ work in UK for first time in decades

The Guardian, August 4, 2024

-